Phage therapy

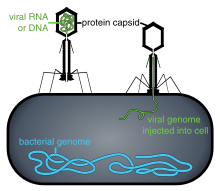

An electron micrograph of bacteriophages attached to a bacterial cell. These viruses are the size and shape of coliphage T1.

Phage therapy or viral phage therapy is the therapeuticuse of bacteriophages to treat pathogenic bacterial infections.[1] Phage therapy has many potential applications in human medicine as well as dentistry, veterinary science, and agriculture.[2] If the target host of a phage therapy treatment is not an animal, the term "biocontrol" (as in phage-mediated biocontrol of bacteria) is usually employed, rather than "phage therapy".

Bacteriophages are much more specific than antibiotics. They are typically harmless not only to the host organism, but also to other beneficial bacteria, such as the gut flora, reducing the chances of opportunistic infections.[3] They have a high therapeutic index, that is, phage therapy would be expected to give rise to few side effects. Because phages replicate in vivo (in cells of living organism), a smaller effective dose can be used. On the other hand, this specificity is also a disadvantage: a phage will only kill a bacterium if it is a match to the specific strain. Consequently, phage mixtures are often applied to improve the chances of success, or samples can be taken and appropriate phages identified and grown.

Phages tend to be more successful than antibiotics where there is a biofilm covered by a polysaccharide layer, which antibiotics typically cannot penetrate.[4] In the West, no therapies are currently authorized for use on humans.[5]

Phages are currently being used therapeutically to treat bacterial infections that do not respond to conventional antibiotics, particularly in Russia[6] and Georgia.[7][8][9] There is also a phage therapy unit in Wrocław, Poland, established 2005, the only such centre in a European Union country.[10]

Contents

History

The discovery of bacteriophages was reported by the Englishman Frederick Twort in 1915[11] and the French-Canadian Felix d'Hérelle in 1917.[12][13] D'Hérelle said that the phages always appeared in the stools of Shigelladysentery patients shortly before they began to recover.[14] He "quickly learned that bacteriophages are found wherever bacteria thrive: in sewers, in rivers that catch waste runoff from pipes, and in the stools of convalescent patients".[15] Phage therapy was immediately recognized by many to be a key way forward for the eradication of pathogenic bacterial infections. A Georgian, George Eliava, was making similar discoveries. He travelled to the Pasteur Institute in Paris where he met d'Hérelle, and in 1923 he founded the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia, devoted to the development of phage therapy. Phage therapy is used in Russia, Georgia and Poland.

In Russia, extensive research and development soon began in this field. In the United States during the 1940s commercialization of phage therapy was undertaken by Eli Lilly and Company.

While knowledge was being accumulated regarding the biology of phages and how to use phage cocktails correctly, early uses of phage therapy were often unreliable.[16] Since the early 20th century, research into the development of viable therapeutic antibiotics had also been underway, and by 1942 the antibiotic penicillin G had been successfully purified and saw use during the Second World War. The drug proved to be extraordinarily effective in the treatment of injured Allied soldiers whose wounds had become infected. By 1944, large-scale production of Penicillin had been made possible, and in 1945 it became publicly available in pharmacies. Due to the drug's success, it was marketed widely in the U.S. and Europe, leading Western scientists to mostly lose interest in further use and study of phage therapy for some time.[17]

Isolated from Western advances in antibiotic production in the 1940s, Russian scientists continued to develop already successful phage therapy to treat the wounds of soldiers in field hospitals. During World War II, the Soviet Union used bacteriophages to treat many soldiers infected with various bacterial diseases e.g. dysentery and gangrene. Russian researchers continued to develop and to refine their treatments and to publish their research and results. However, due to the scientific barriers of the Cold War, this knowledge was not translated and did not proliferate across the world.[18][19] A summary of these publications was published in English in 2009 in "A Literature Review of the Practical Application of Bacteriophage Research".[20]

There is an extensive library and research center at the George Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia. Phage therapy is today a widespread form of treatment in that region.[21]

As a result of the development of antibiotic resistance since the 1950s and an advancement of scientific knowledge, there has been renewed interest worldwide in the ability of phage therapy to eradicate bacterial infections and chronic polymicrobial biofilm (including in industrial situations[22]).

Phages have been investigated as a potential means to eliminate pathogens like Campylobacter in raw food[23] and Listeria in fresh food or to reduce food spoilage bacteria.[24] In agricultural practice phages were used to fight pathogens like Campylobacter, Escherichia and Salmonella in farm animals, Lactococcus and Vibriopathogens in fish from aquaculture and Erwinia and Xanthomonas in plants of agricultural importance. The oldest use was, however, in human medicine. Phages have been used against diarrheal diseases caused by E. coli, Shigella or Vibrio and against wound infections caused by facultative pathogens of the skin like staphylococci and streptococci. Recently the phage therapy approach has been applied to systemic and even intracellular infections and the addition of non-replicating phage and isolated phage enzymes like lysins to the antimicrobial arsenal. However, actual proof for the efficacy of these phage approaches in the field or the hospital is not available.[24]

Some of the interest in the West can be traced back to 1994, when Soothill demonstrated (in an animal model) that the use of phages could improve the success of skin grafts by reducing the underlying Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection.[25] Recent studies have provided additional support for these findings in the model system.[26]

Although not "phage therapy" in the original sense, the use of phages as delivery mechanisms for traditional antibiotics constitutes another possible therapeutic use.[27][28]The use of phages to deliver antitumor agents has also been described in preliminary in vitroexperiments for cells in tissue culture.[29]

Potential benefits

Phage therapy is the use of bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections. This could be used as an alternative to antibiotics when bacteria develops resistance. Superbugs that are immune to multiple types of drugs are becoming a concern with the more frequent use of antibiotics. Phages can target these dangerous microbes without harming human cells due to how specific they are.

Bacteriophage treatment offers a possible alternative to conventional antibiotic treatments for bacterial infection.[32] It is conceivable that, although bacteria can develop resistance to phage, the resistance might be easier to overcome than resistance to antibiotics.[33][34]Just as bacteria can evolve resistance, viruses can evolve to overcome resistance.[35]

Bacteriophages are very specific, targeting only one or a few strains of bacteria.[36] Traditional antibiotics have more wide-ranging effect, killing both harmful bacteria and useful bacteria such as those facilitating food digestion. The species and strain specificity of bacteriophages makes it unlikely that harmless or useful bacteria will be killed when fighting an infection.[citation needed]

A few research groups in the West are engineering a broader spectrum phage, and also a variety of forms of MRSA treatments, including impregnated wound dressings, preventative treatment for burn victims, phage-impregnated sutures.[37][34] Enzybiotics are a new development at Rockefeller University that create enzymes from phage. Purified recombinant phage enzymes can be used as separate antibacterial agents in their own right.[38]

Application

Collection

The simplest method of phage treatment involves collecting local samples of water likely to contain high quantities of bacteria and bacteriophages, for example effluent outlets, sewageand other sources.[7] The samples are taken and applied to the bacteria that are to be destroyed which have been cultured on growth medium.

If the bacteria die, as usually happens, the mixture is centrifuged; the phages collect on the top of the mixture and can be drawn off.

The phage solutions are then tested to see which ones show growth suppression effects (lysogeny) or destruction (lysis) of the target bacteria. The phage showing lysis are then amplified on cultures of the target bacteria, passed through a filter to remove all but the phages, then distributed.

Treatment

Phages are "bacterium-specific" and it is therefore necessary in many cases to take a swab from the patient and culture it prior to treatment. Occasionally, isolation of therapeutic phages can require a few months to complete, but clinics generally keep supplies of phage cocktails for the most common bacterial strains in a geographical area.