The Wild Bunch

Two years after a deadly Waco shoot-out, the local district attorney is trying to take down the Bandidos and Cossacks biker clubs. It won’t be easy.

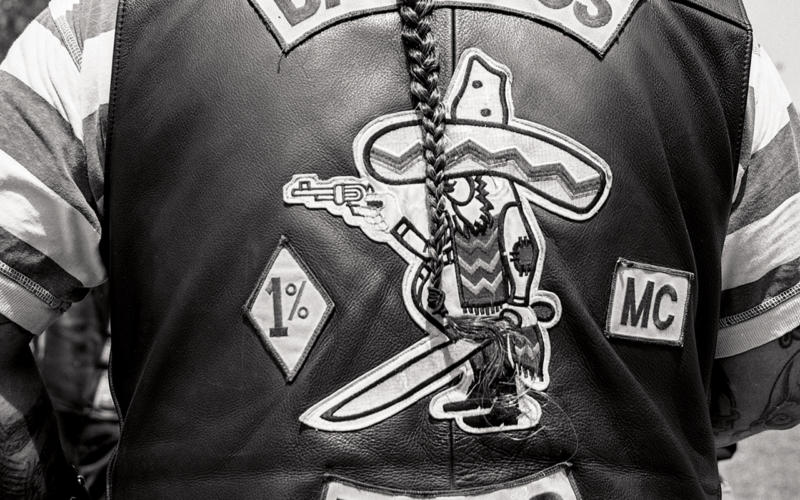

It started off as a Texas version of the Sharks versus the Jets. In 2013, the Bandidos, the oldest, biggest, and most-feared outlaw motorcycle club in the state, learned that members of the Cossacks, a rapidly growing rival club, had begun wearing patches on the backs of their vests that read “Texas” in capital letters. For decades, the Bandidos had decreed that the Texas “bottom rocker” patch belonged only to them. If another club wanted to wear the patch, it would have to receive permission from the Bandidos and pay them dues. But the Cossacks contended that the Bandidos had no right to tell them what to do.

For two years, the clubs skirmished. Outside a steakhouse in Abilene, ten Bandidos and their associates assaulted and stabbed at least four Cossacks. In the town of Lorena, a group of Cossacks forced a Bandido off Interstate 35 and beat him with chains and metal pipes. At a gas station near the town of Gordon, an estimated twenty Bandidos confronted a Cossack, and when he refused to give them his vest with its Texas patch, he was beaten and struck in the head with a claw hammer.

In May 2015, word got out that Bandidos and Cossacks from around the state would be coming to Waco for the quarterly meeting of the Texas Confederation of Clubs and Independents, a bikers’ organization. The meeting was being held at, of all places, a Twin Peaks, one of those Hooters-like “breastaurants” where waitresses dress in midriff-baring and cleavage-revealing outfits.

On May 17, the day of the meeting, at least sixty Cossacks (along with members of a couple of other clubs that had aligned with them) showed up early at Twin Peaks and took over most of the seats on the patio. Several Waco policemen and Texas Department of Public Safety troopers, who had learned that a potential confrontation was brewing, also arrived, and positioned themselves in a grassy area overlooking the restaurant.

Close to high noon, a line of Bandidos thundered toward Twin Peaks on their Harley-Davidsons. One of the Bandidos’ bikes either struck or nearly struck a prospective member of the Cossacks in the parking lot. Cossacks bounded over the patio railings, and the Bandidos were ready for them. It looked like something straight out of a Sam Peckinpah movie. Wielding clubs, brass knuckles, baseball bats, knives, and handguns, the bikers beat, stabbed, and shot one another. Three officers grabbed their rifles and opened fire, bringing down as many as four bikers. Inside Twin Peaks, there was complete pandemonium. Waitresses, bikers, and other customers dove for cover. Several people hid in the bathrooms.

The battle lasted no longer than a minute or two. When it was over, nine bikers lay dead in the parking lot. Eighteen others were injured. “In thirty-four years of law enforcement, this is the most violent crime scene I have ever been involved in,” Waco police Sergeant W. Patrick Swanton told members of the news media. “There is blood everywhere.”

The police detained 239 people and had them taken in buses to the Waco Convention Center, which had been turned into a temporary holding facility. Reporters assumed that detectives would be arresting only those bikers who were directly involved in the fight: maybe a couple dozen of the survivors. But at the recommendation of McLennan County District Attorney Abel Reyna, 177 bikers—all of them Bandidos, Cossacks, or men believed to be supporters of one of the two clubs—were arrested and charged with the exact same offense: “engaging in organized criminal activity,” a first-degree felony punishable by sentences ranging from fifteen years to life. A justice of the peace set identical bonds for the bikers—$1 million each—and they were hauled off to the county jail. It was one of the largest mass arrests over a single criminal incident in American history.

Over the next few months, the bonds were reduced. Twenty-two bikers had their charges dropped because of a lack of evidence connecting them to the Bandidos or Cossacks. Still, 155 bikers were eventually indicted by a grand jury. This month, nearly two years after the Twin Peaks melee, the first of the cases is scheduled to go to trial. (According to court filings, Reyna plans to try a Bandido, whose name has not yet been publicly revealed.) That trial, presumably, will be followed by another one, and then another and another, on and on—enough cases to fill up the dockets of two of Waco’s state district courts for at least two years.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ROD AYDELOTTE/WACO TRIBUNE HERALD VIA AP

A decade ago, when I first wrote about the Bandidos (“The Gang’s All Here,” April 2007), law enforcement officials told me that the Houston-based club, which was started in 1966, was not all that different from a Mafia family. They believed that the Bandidos ran guns and drugs, extorted money from the owners of roadhouses and strip joints, and assaulted and occasionally murdered those who crossed them. Periodically, Bandidos were convicted of crimes, but the cops could never bring down the club. It continued to prosper, reaching 1,100 members (nearly half of them in Texas) by the time of the Twin Peaks fight.

The Cossacks, who got their start in 1969, in East Texas, mostly stayed under the public radar. But over the past decade, as they began to grow, drawing in younger, more aggressive members, they too attracted the attention of law enforcement. Like the Bandidos, however, the club itself didn’t suffer. Prior to the Twin Peaks fight, the Cossacks reportedly were three hundred to four hundred members strong, and they were actively seeking new recruits.

Enter Reyna. A member of a well-regarded Waco family—his father was the McLennan County district attorney in the late eighties and later a judge on the Tenth Court of Appeals—the 44-year-old Republican was elected district attorney in 2010, beating a longtime Democratic incumbent. Burly and affable, he’s known for his ability to connect with jurors. One reporter who covers the courthouse told me that he recently watched Reyna spend less than twenty minutes at a trial studying a list of sixty or so potential jurors. Then, during the voir dire examination, he called every person on that list by name, chatting pleasantly with them about their lives without once looking at his notes.

At the same time, Reyna is also known to be unyielding at trial, demanding harsh sentences even for first-time offenders. And in the aftermath of the Twin Peaks shooting, he made it clear he had little sympathy for any of the bikers who happened to be at the restaurant. In fact, Reyna had an opportunity to do something no other district attorney in Texas had ever done: seriously cripple the Bandidos and Cossacks in one fell swoop.

Reyna turned to the state’s organized-criminal-activity statute, which had originally been passed by the Legislature to make it easier for police and prosecutors to go after what the statute described as a “criminal street gang,” like the Crips or the Bloods. (The statute defines a criminal street gang as “three or more persons having a common identifying sign or symbol or an identifiable leadership who continuously or regularly associate in the commission of criminal activities.”) Reyna claimed that both the Bandidos and Cossacks were criminal street gangs and that they had come to Twin Peaks to commit or to conspire to commit organized criminal activity, namely murder and assault. According to Reyna, even those Bandidos and Cossacks (and their respective supporters) who didn’t directly participate in the fight were in violation of the statute because they were there to support their gang. As Michael Jarrett, Reyna’s first assistant district attorney, explained in one court hearing: “The act of engaging in organized crime was committed when these people showed up in our fair county with the intent to show themselves as a show of force, both the Cossacks and their ilk and the Bandidos and their ilk.”

Reyna isn’t talking to the news media. But defense attorneys—nearly one hundred have been retained or appointed by the court—are in an uproar. They claim Reyna is going after their clients with no evidence whatsoever that they did anything wrong. “The district attorney seems to have an egomaniacal need to do something big so he can get his fifteen minutes of fame,” said Paul Looney, a well-regarded Houston attorney who represents one of the indicted bikers. “He wants to do something no one has ever done on a scale that has not been accomplished, and in the process, he’s tortured the law and he’s tortured the facts. The only thing he has accomplished is chaos.”

What most infuriates the defense attorneys are Reyna’s attempts to label the motorcycle clubs as criminal street gangs. Yes, the attorneys acknowledge, a few of the members had, on their own, committed crimes. But the majority of the men were law-abiding citizens who had no criminal records and who simply liked to go on long weekend rides with their fellow members.

What’s more, the attorneys argue, the Bandidos and Cossacks (and their respective supporters) didn’t go to Twin Peaks as part of some prearranged plan to fight their rivals. They were there only to socialize and to hear speakers discuss such topics as motorcycle-safety initiatives. The brief fight in the parking lot, the attorneys contend, was the result of an unexpected confrontation among a few hotheaded Bandidos and Cossacks that spiraled out of control. “The rest of the bikers were not even near the parking lot,” said Looney. “When they heard gunshots, they ran the other way. They were scared. How Reyna can claim that those bikers were conspiring to commit murder or assault is beyond my comprehension.”

Defense attorneys have filed at least twenty federal civil rights lawsuits against Reyna and then–Waco police chief Brent Stroman (who retired last year), charging that they and their surrogates didn’t even try to establish probable cause when they arrested the bikers. Instead, the lawsuits allege, the officials relied on generic affidavits, filled out by one police detective, that provided no specific evidence about what crime was supposedly committed by each biker. A lawsuit filed by Clint Broden and Don Tittle, Dallas attorneys who represent more than twenty of the bikers, claims that Reyna and Stroman “theorized that a conspiracy of epic proportion between dozens of people had taken place, and willfully ignored the total absence of facts to support their ‘theory.’ ” When I asked Broden if he believes Reyna knew he had gone too far when he orchestrated the mass arrests of the bikers, he replied, “I can’t get into Reyna’s head, but many mistakes were made.”

Broden and other attorneys have also filed motions in state district court seeking to disqualify Reyna and two of his top assistants from prosecuting the Twin Peaks cases. (They believe the prosecutors are potential witnesses in the trials because of the way they inserted themselves into the investigation after the shoot-out.) In a brief comment Reyna made to Texas Lawyer, he dismissed the attempts to remove him as “shenanigans.” And according to those who are close to him, he’s itching to get the trials started. He seems convinced that he will win his first couple of trials, which he believes will inspire the other indicted bikers to make plea deals.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ROD AYDELOTTE/WACO TRIBUNE-HERALD VIA AP

If such a scenario happens, Reyna will become one of Texas’s most celebrated prosecutors: the district attorney who took on the outlaw bikers. But if he loses, a lot of people will be calling him a fool. “A complete fool,” said Looney. “There’s nothing else to be said.”

As for the residents of Waco, they seem ready for the whole legal mess to go away. “Tying up our courtrooms for so long over some bikers?” one Waco man said to me. “A lot of people I know are saying, ‘No, thank you.’ ”

Some citizens have told reporters that they would like to see Twin Peaks demolished to help erase the memories of what happened. Although the restaurant closed after the shooting, the building is still standing, with No Trespassing signs posted out front. On weekends, curious visitors to Waco sometimes pull off I-35 and drive past, craning their necks to get a better look. Occasionally, a friend or family member of one of the bikers who died shows up and leaves behind a makeshift memorial: a bouquet of flowers, a card with a photograph, a wooden cross, chains or other trinkets. The memorials are regularly carted away by police officers or security guards from the nearby shopping center (apparently they are under orders to keep the building from being turned into a sort of sacred biker shrine). But the mourners always return, shaking their heads and wiping tears from their eyes.

Since the Twin Peaks fight, the Bandidos and Cossacks have been laying low, avoiding any confrontations, waiting to see what happens in court. In January 2016 the Bandidos suffered another serious blow when the club’s lead officers, including longtime president Jeff Pike, were indicted by a federal grand jury in San Antonio for allegedly sanctioning the commission of numerous crimes by their members, including extortion, drug trafficking, and assault and murder, in order to protect and enhance “the organization’s power, territory, reputation, and profits.” (None of the officers were charged in the Twin Peaks cases.) Early last month, four more Bandidos were arrested for the 2006 killing of a rival biker in Austin.

But anyone who thinks that any of this will bring down the Bandidos should think again. A former Texas Department of Public Safety official who investigated motorcycle clubs for fifteen years told me that another group of Bandidos has already stepped up to lead the club. “And they are just as badass as the previous officers,” he said. “Listen, the Bandidos aren’t going away. And neither are the Cossacks. Outsiders don’t understand: these bikers are more loyal to their clubs than they are to their own families. Outsiders also don’t understand that these guys have very long memories.”

When I asked him what exactly he meant, he said, “None of them are ever going to forget about Twin Peaks. For them, there is still unresolved business from that day. And no matter what law enforcement tries to do, and no matter who gets sent off to prison, the Bandidos and Cossacks will go at it again. Somewhere down the road, they’ll fight again. That’s just the biker way.”

No comments:

Post a Comment