Wednesday, March 25, 2020

Curr Opin Immunol. 2018 Dec;55:89-96. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.09.016. Epub 2018 Nov 15.

Bridging the gap between vaccination with Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and immunological tolerance: the cases of type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis.

Abstract

At the end of past century, when the prevailing view was that treatment of autoimmunity required immune suppression, experimental evidence suggested an approach of immune-stimulation such as with the BCG vaccine in type 1 diabetes (T1D) and multiple sclerosis (MS). Translating these basic studies into clinical trials, we showed the following: BCG harnessed the immune system to 'permanently' lower blood sugar, even in advanced T1D; BCG appeared to delay the disease progression in early MS; the effects were long-lasting (years after vaccination) in both diseases. The recently demonstrated capacity of BCG to boost glycolysis may explain both the improvement of metabolic indexes in T1D, and the more efficient generation of inducible regulatory T cells, which counteract the autoimmune attack and foster repair mechanisms.

Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Angelo Biglioli and Giuseppina Oggioni photographed last year by their grandson. Both died within days of each other after battling the coronavirus. MICHELE BIGLIOLI

ROME—The first call came on March 11. That’s when Roberto Biglioli says he found out that his 81-year-old mother, Giuseppina, had passed away after battling the new coronavirus.

The second call came six days later, says Mr. Biglioli, a medical worker from near Bergamo, a northern Italian city hit hard by the pandemic. “A call that, while expected, no one would ever want to receive in their lifetime,” he said. “My dear dad has also left us.”

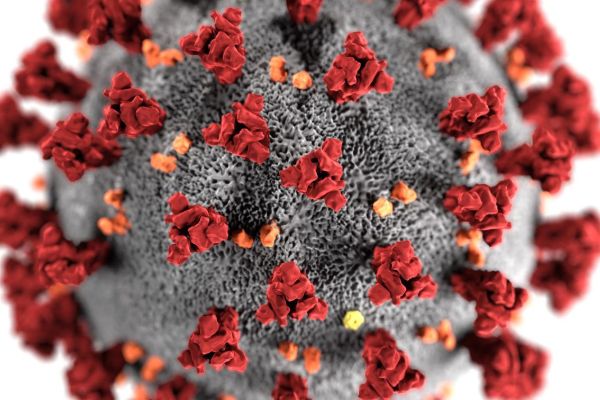

Italians across the peninsula are terrified their own parents or grandparents will be next. They have reason to worry. Covid-19, the respiratory disease caused by the new coronavirus, has killed more people in Italy than anywhere else in the world, and the victims were overwhelmingly over 60.

Now, the whole country is hunkering down to protect them. The severe restrictions placed on daily life are shaking the very bedrock of Italian society: The Italian family.

Italy’s way of life makes it unique in the West, and has helped power the country through times of upheaval and strife. It also left Italy far more vulnerable to the pandemic.

Two or three generations often live under the same roof, more so than in other parts of Western Europe. It’s common for grandparents to look after their grandchildren on a daily basis, and for their adult children to look after them, once they become older. Now, efforts to combat the virus are putting an enormous strain on this social safety net.

“Our habits need to change, and they need to change now,” Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte said on March 10, when Italy became the first Western country to impose a nationwide lockdown. “We all need to give something up for the good of Italy. When I speak of Italy I speak of the people who are dear to us, our parents, our grandparents.”

Italy’s 60 million residents are forced to stay at home unless they can prove they need to be out, for instance to work or to buy essential goods, like groceries or drugs. Italians over the age of 65— around 14 million people, nearly a quarter of the population—are discouraged from doing even that. Everyone else has been told to stay away from them to protect them from infection.

Umberto Cremasoli, 77, and his wife used to see their twin granddaughters almost every day. After doctors discovered a coronavirus infection near their hometown of Casalpusterlengo on Feb. 20—the first in Italy’s outbreak—the elderly couple saw the two toddlers even more than usual.

The government responded to the outbreak by shutting down all schools and nurseries in their area. So the elderly couple looked after the two toddlers while their parents worked. As the number of sick in the surrounding region of Lombardy continued to rise, even seeing the children became too risky.

These days, no one is allowed into their apartment, not even their grandchildren, as they too could be carriers. The couple never go out. They have groceries and drugs delivered to their front door.

“We live in terror,” said Mr. Cremasoli. “‘You may have it and you may infect me’. That’s the feeling we all have.”

Umberto Cremasoli and his wife, Maria Antonietta Scarioni, were active but now isolate themselves at home. The virus ‘has turned our life upside down.’

Before the outbreak, Mr. Cremasoli and his wife had an active social life. His wife, Maria Antonietta Scarioni, 68,used to meet up with friends at a local café almost daily. She also took Spanish language classes and ballroom dancing lessons at a community center for the elderly.

She knows of at least three people from the community center who got sick, two of whom died. “One of them,” she says, “was a great dancer.”

“It turned our life upside down because we are forced to stay at home,” she adds. “But we have to follow the rules.”

Global data shows that the new coronavirus is much deadlier for the old than it is for the young. That’s particularly troubling for Italy, which has the world’s second-oldest population after Japan, and helps explain why the country’s death toll for the disease is now the highest in the world, having surpassed even China’s.

Of the nearly 69,200 people who are known to have been infected with the virus in Italy, 6,820 have died. So far, the disease has spared children and teens, with zero deaths recorded under the age of 20, according to data from Italy’s National Health Institute, the country’s top disease-control body.

The number of dead starts climbing rapidly after the age of 60. In Italy, some 16% of people in their 70s who have tested positive to the coronavirus so far have died. For those in their 80s, the percentage is even higher, 24%.

The true fatality rates are likely lower, even within those age groups, since testing for the virus is mostly limited to those who show clear symptoms, meaning a possibly vast number of cases are not being counted, according to health experts.

A woman and her child greet the grandfather from a safe distance in Cremona, Italy. The country is rallying to save its older generations hit hardest by the deadly virus.

In Lombardy, the northern region at the heart of Italy’s outbreak, the health-care system is so overstretched that doctors aren’t able to treat all patients who need care. In towns such as Bergamo and Brescia, doctors have been forced to choose who to give the last available beds in intensive-care units, privileging the younger and healthier patients over the older and frailer ones.

Aware that their older relatives might get only limited medical treatment, the priority for many Italian families is to make sure they never get sick at all.

Gianna Besson, 70, has been housebound for over two weeks, ever since her two sons forbade her from leaving her flat in Rome’s Trastevere neighborhood. One of her sons lives in her same building, but is frantic about not coming near her. He leaves food and medicine for her outside her door, rings the bell and disappears before she has a chance to open it. To limit her exposure to the virus, the cleaning lady is no longer coming.

“They decided I have to remain cooped up in my flat because I am more at risk than they are. I am reluctantly complying with their orders,” says Ms. Besson, who until the lockdown was busy with projects that ranged from documentary filmmaking to ceramics classes.

Loneliness has been the hardest thing to get used to for Ms. Besson. “I feel the need to have physical contact with someone. It doesn’t even have to be a hug, it could just be the touch of a hand,” she says. “I’m very tempted to leave the house with the excuse of having to go to the pharmacy. I’m very tempted. If I didn’t have children, I would’ve gone out.”

Umberto Cremasoli picks up medication that his son left on the front door of the house for him. Italians are urged to isolate to protect their parents and grandparents.

In the northern city of Turin, in the foothills of the Alps, 64-year-old Anna Marcone is doing everything she can to insulate her own, 94-year-old mother from the outside world. The physiotherapist had to suspend their twice weekly sessions. The hairdresser, who came once a week, has stopped coming, too. Medical checkups have also been put on hold.

These days, it’s Ms. Marcone who helps her mother with physiotherapy and who does her hair. “I’ve become a perfect coiffeuse,” says Ms. Marcone, who has lived with her mother for decades. Until two years ago, so did her son Paolo.

“She’s been such a big part of my life that I don’t even consider her my grandmother. She’s more than that,” says Paolo Mussa, 31, who until last week would join his grandmother for regular meals. For the time being, they communicate through video chats instead.

“The least you can do is to protect them,” says Ms. Marcone. “We are very conscious of what they did for us, so we are happy to be doing this for them. Love makes everything easier.”

Multi-generational households like Ms. Marcone’s are much more common in Italy than in other Western countries. In Italy, around 23% of between the ages of 30 and 49 live with their parents, compared to just 6.4% in the U.S., 5.2% in the U.K or 1% in neighboring France, according to data compiled by the University of Bonn.

Above, a pharmacy in the provice of Lodi, Italy; below, an empty newsstand. Italians are being urged to stay inside, especially to protect the elderly.

Such living arrangements risk increasing the exposure of the elderly to the virus. Close contact between members of different generations in Italy could help explain why so many old people here are dying, according to a new research paper on the transmission of Covid-19, which found a correlation between countries where multi-generational households are common and higher fatality rates.

“If you share a house, it’s very likely that other people will get it. But it applies more generally: What role do grandparents play in everyday life, in the organization of families?” says Christian Bayer, a professor of economics at the University of Bonn who co-authored the paper. “It’s not that in northern Europe you lock away the elderly, but maybe you don’t meet them on a day-by-day basis.”

Italy’s experience is a warning sign for other regions where the virus is beginning to take hold with similar setups and traditions, such as the Middle East and Southern Europe.

The Italian government in early March took what it believed was a first, drastic step to help prevent children from infecting their grandparents: It shut down nurseries, schools and universities across the country. Public health officials explained that while children with Covid-19 rarely show severe symptoms, they wanted to prevent them from becoming infected and then spreading the disease to their grandparents.

For many families, grandparents were the obvious solution for children whose parents continued working. But as deaths mounted, the government urged Italians to leave grandparents alone, and offered families vouchers to pay for babysitters instead. Italians began engineering a painful and logistically complicated separation.

Mr. Biglioli, the medical worker from Bergamo who lost both his parents to Covid-19, says sacrifices are worth it.

Like many Italians, Mr. Biglioli lived in the same small town as his parents. His father Angelo was the unofficial photographer of Romano di Lombardia, a town of some 20,000 people south of Bergamo, documenting christenings, weddings and daily life there. Photography is a skill he taught his son and his grandson, Michele, from a young age.

“He used to gift me disposable cameras and take me into the darkroom with him,” recalls Michele Biglioli, 28, who—along with his parents and younger brother—lived with his grandparents until the age of 14.

Italy on Lockdown: Crowdless Soccer Games and Deserted Streets

UP NEXT

0:00 / 2:09

Italy on Lockdown: Crowdless Soccer Games and Deserted Streets

He continued to see them almost daily until a few weeks before they died, and took pictures of the aging couple.

“They were my main subjects,” says Michele. “My grandparents were like parents to me. They were friends, a shoulder to lean on. When the world turned against me, they were always there for me.”

When the couple developed the first symptoms, health authorities instructed them to self-isolate. No doctor came to visit them. Giuseppina Oggioni passed away in her home on March 11. Later that same day, Michele, his younger brother and their father rushed Angelo Biglioli to the hospital, in a last, desperate attempt to save him. In the waiting room, Angelo stroked Michele’s hand and told them all he loved them. They never saw each other again.

“Only leave your homes if you absolutely have to,” said Roberto Biglioli. “Do it out of respect for those who are no longer here with us, those who died because of this damned virus. Do it for those who are fighting for their lives in hospitals all over Italy. Above all, do it for yourselves.”

For Luigi Carbone, 60, staying away from his three grandsons is almost impossible: They all live in the same building, two floors apart. The children used to regularly come over after school to do their homework and sometimes slept over.

“We basically lived together,” said Mr. Carbone, whose profile photo on WhatsApp is a wooden heart gifted by his grandchildren—one of whom is named after him—that says “Best Granddad in the World.”

That changed when the Italian government on March 10 imposed strict restrictions on movement across Italy, a step partly aimed to stop the disease from quickly reaching poorer southern regions such as Puglia, where Mr. Carbone lives, which are less-equipped to deal with a health emergency.

Before the government enforced the lockdown, tens of thousands of southern students and workers living in northern Italy rushed to join their families in the south – and infected many of their older relatives, according to local health officials.

For the time being, the situation in Puglia isn’t as dramatic as it is in the north, with a relatively small number of coronavirus cases confirmed so far.

The extended Carbone family is gradually getting used to the new rules. They no longer see each other daily, and when they do, they don’t get too close.

“When we see each other, we don’t hug anymore. We try to keep a distance,” says Anna, Mr. Carbone’s wife. “It’s really hard.”

“Stay strong, everything will be all right!” Italians in the north of the country have been hit hard by the virus.

Write to Margherita Stancati at margherita.stancati@wsj.com

Copyright ©2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

WSJ opens select articles to reader conversation to promote thoughtful dialogue. See the 'Join the Conversation' area for stories open to conversation. For more information, please reference our community guidelines. Email feedback and questions to moderator@wsj.com.

SPONSORED OFFERS

No comments:

Post a Comment