The hell with the quality of care and lack of art dispensed by Mike

see faustmanlab.org , pubmed.org faustman dl, and pubmed.org ristori + bcg

don't die for Mike and his marketing

Ristori

G, Romano S, Cannoni S, Visconti A, Tinelli E, Mendozzi L, Cecconi P,

Lanzillo R, Quarantelli M, Buttinelli C, Gasperini C, Frontoni M,

Coarelli G, Caputo D, Bresciamorra V, Vanacore N, Pozzilli C, Salvetti

M.

Neurology. 2014 Jan 7;82(1):41-8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000438216.93319.ab. Epub 2013 Dec 4.

- PMID:

- 24306002

- [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

North Shore-LIJ CEO Michael Dowling is scripting a new model for health care

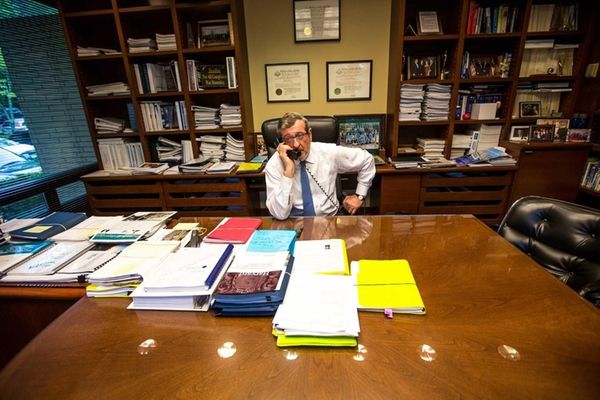

Michael J. Dowling, president and chief executive

of the North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System, at his office in

Manhasset on May 22, 2014. (Credit: Uli Seit)

Related media

17 times LI faced off with NJ over businesses

17 times LI faced off with NJ over businesses

Data and Map: LI's retail bank branches

Data and Map: LI's retail bank branches

See where the job growth will be for LI

See where the job growth will be for LI

See where jobs are on LI

See where jobs are on LI

Complete coverage: LI business

Complete coverage: LI business

Latest business videos

Latest business videos

Travel deals

If North Shore-LIJ were ranked among public companies, its 2013 operating revenue of $7 billion would make it No. 2 on Long Island, behind health care products provider Henry Schein Inc. Its 48,000 employees -- predominantly on the Island, but also throughout the metropolitan area -- would overflow Citi Field.

Still, few view the sprawling not-for-profit corporation through the lens of business; yet it's a perspective Dowling unapologetically embraces.

MARKET LINKS: Live Market Summary | Earnings News | Popular Mutual Funds | Check Bonds | Energy/Metal Futures | Press Releases

Dowling, 64, grew up in a thatched cottage with a dirt floor in County Limerick, Ireland. At 17, he ventured to the United States, working on the Manhattan docks. He returned to Ireland to earn a bachelor's degree from University College Cork before coming back to New York for a master's degree in social work at Fordham University. In 1983 he joined the administration of New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, serving as director of Health, Education and Human Services and commissioner of the Department of Social Services. In 2002 he was named CEO of North Shore-LIJ.

In a series of conversations, Newsday asked the Northport resident how he is cobbling together a health care colossus; how he wants to change the financial model for health care to encourage wellness and prevention; and what the Long Island economy could learn from North Shore-LIJ.

Q:You generate billions in revenue, yet you're structured as a not-for-profit. How do you balance the needs of serving a community with commercial imperatives?

A: We're a business. I can't do good things unless the fundamentals are working. I run it as a business and I'm not ashamed to say it, because that's the only way I can do the things I want to do and the things that are good for the community. A lot of what we do loses money. We're one of the largest providers of mental health services. It loses money because it's [largely funded by Medicare and] Medicaid. But I have to continue to expand my mental health services because it's so necessary for the community.

Q:You've grown over the years by acquisitions. Where do you operate now, and are you still growing?

A: Our home is Long Island, but we cover the five boroughs, and we're in New Jersey [through an alliance with Hackensack University Health Network]. And we'll expand even more.We're in negotiations with Phelps Memorial Hospital Center in Westchester now. There will be more expansion in the city, because the opportunities in Manhattan are great. We're in discussions in Connecticut, New Jersey and Orange, Putnam and Rockland counties. If you look at what's happening in health care around the country, you'll have no small entities left.

Q:How do you wring efficiencies from merged hospitals and other pieces of the health system?

A: All the back office functions are consolidated. We have common standards across the whole health system for quality, service, financial performance, etc. We have the only truly integrated health system in New York State. There's nobody else close.

Q: You're an advocate of changing health care from a "transactional" model, where payments are made for treating sick people, to one where there's more incentive to prevent sickness. Please explain how that would work.

A: The way medical care has operated, hospitals were at the center of the universe. You got sick, you went to the hospital. When you got sick, we got paid. If you got sick twice, we got paid twice. If you had shoulder surgery, we got paid. If you had knee surgery, we got paid. This still exists, by the way.

You want to move to a system whereby you're responsible for the holistic management of a person's health and get paid and have the ability to do prevention, wellness promotion, have people taken care of in the appropriate location and not necessarily have everybody going to a hospital.

I had five surgeries last year. Two back surgeries, knee surgery, shoulder surgery, a pulmonary embolism. Five years ago I would have gone into a hospital [for the shoulder surgery]. I'd have stayed there for three days. Last Dec. 18, I go in the morning at 6 o'clock. I'm in an ambulatory site. The surgery took over four hours. They had to rebuild the shoulder. And I was home on my couch at Northport at 3 o'clock in the afternoon. There was no need for me to be in a hospital bed. Most surgery is now done in ambulatory locations. My guess is 10 years from now, 60 percent of all our care delivery will be outside the four walls of a hospital. Now it's [roughly 40] percent out and 60 percent in.

Q: How does your insurance unit figure in your plans to move away from fee-for-service health care?

A: The traditional way is an insurance company will collect a dollar from you, and then I negotiate with them and I'll get a small percentage of that dollar.

[But] if I get the bulk of the premium dollar or the total premium dollar [as an insurer], I then can be in the business of promoting health and managing a person's health as well as treating illness.

Q: How long will this take?

A: Our insurance company is small. We have 10,500 members. Our goal is to have in excess of 20,000 members by the end of the year. Eventually, I can have my own employees in the insurance plan. I'm talking about a 10-year transition. I want to go upstream and get the premium dollar. This is not unique across the country. Everybody says: How is [Oakland, Calif., health care system] Kaiser Permanente able to do so many innovative things? They've had their own insurance company.

Q: Is your entry into the insurance business a factor in your merger drive?

A: I can't sell insurance to you if half of your employees live in Westchester [and I don't have medical facilities there]. I have to have a network of services in those areas where people reside.

Q: North Shore-LIJ is growing, and so is its workforce. How do you maintain the organization's culture?

A: We're a huge economic driver in the community. We hire over 100 people a week. I meet [all new hires] every Monday morning. You onboard people well, select the right people, put the right leadership in place, constantly communicate, weed out people not committed to the organization. But it's constant, constant work.

Q: How could the lessons you've learned in health care be applied to Long Island's economy?

A: We've got to find ways to keep the young people local so they don't necessarily have to leave for employment or enjoyment. We need to make housing available, especially for the young people. We also need to reorganize government. We have multiple silos of government that need to be streamlined. We put all of these independent, separate, distinct hospitals together into one entity. The same could be done for local government units.

Q: U.S. health care is perceived by many as a disaster. Do you share that view?

A: We've got a lot of problems, but everyone forgets the dramatic success. You're living 35 years longer today than people born in 1900. The problem is we're having trouble affording it. It's not a crisis of failure; it's a crisis of success. I have three stents because I had a 95 percent blockage in one artery and an 84 percent block in a second and a 95 percent block in my main artery. Twenty years ago, I would be dead. Stents didn't come in until the early 1980s. If it was 1981 and I had this problem, what they told you to do was go home, put your legs up and rest . . . and maybe drink.

Q: With such a large organization, isn't there a danger of complacency?

A: You keep working at it all the time. No organization is ever perfect. As [football coach] Vince Lombardi once said: Perfection is not achievable; but if you chase perfection, you get excellence.

No comments:

Post a Comment